News

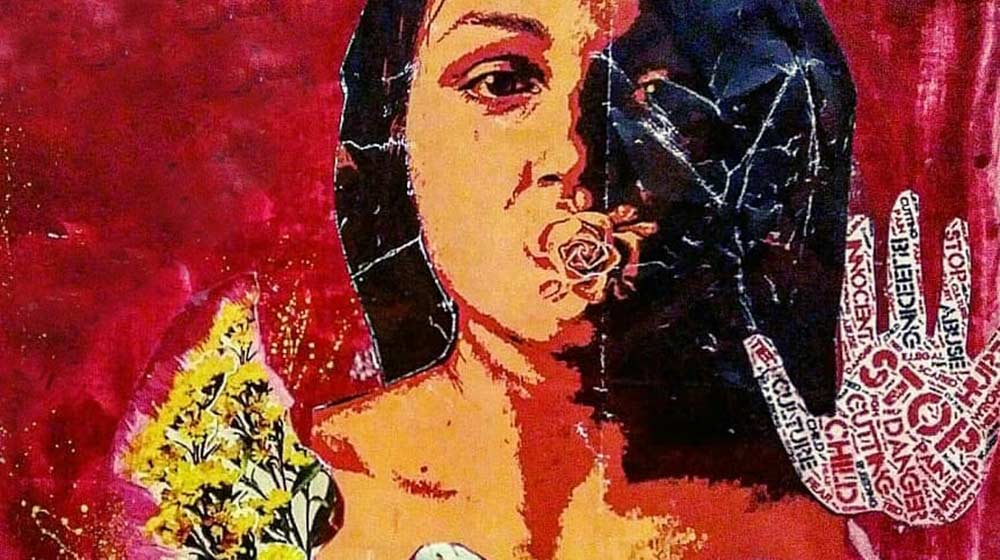

Five things you didn’t know about practices that harm girls

30 June 2020UNITED NATIONS, New York – Every day, hundreds of thousands of girls around the world are harmed physically or psychologically, with the full knowledge and consent of their families, friends and communities. And without urgent action, the situation is likely to worsen.

These are the findings of UNFPA’s flagship 2020 State of World Population report, released today. The report examines the origin and extent of harmful practices around the world, and what must be done to stop them.

It identifies 19 harmful practices – ranging from breast ironing to virginity testing – that are considered to be human rights violations. But it focuses on three practices in particular that are widespread and persistent, despite near-universal condemnation: female genital mutilation (FGM), child marriage and son preference.

Below are five unexpected, and critical, takeaways from the report.

1. People who subject their daughters to these practices are often well intentioned.

Child marriage, FGM and son preference – which can be expressed as gender-biased sex selection or postnatal sex selection – cause profound and lasting harms. They can even be deadly.

Yet these practices are generally not performed out of malice. Rather, they are seen as being in the best interest of the family, or in the best interest of the girl herself.

Child marriage may be intended to secure a girl's future by making her husband’s family responsible for her care. It may be seen as a way to protect her from sexual violence, or as a way to safeguard her reputation if she becomes pregnant. FGM is often performed to ensure a girl is accepted by her future spouse or by the broader community. And families may choose to have boys over girls in communities where sons alone are tasked with caring for their ageing parents or carrying on the family name.

“Good intentions, however, mean little to the girl who must abandon school and her friends to be forcibly wed, or to the girl who faces a lifetime of health problems because of mutilation from a harmful rite of passage,” said UNFPA’s Executive Director, Dr. Natalia Kanem, in her foreword to the report.

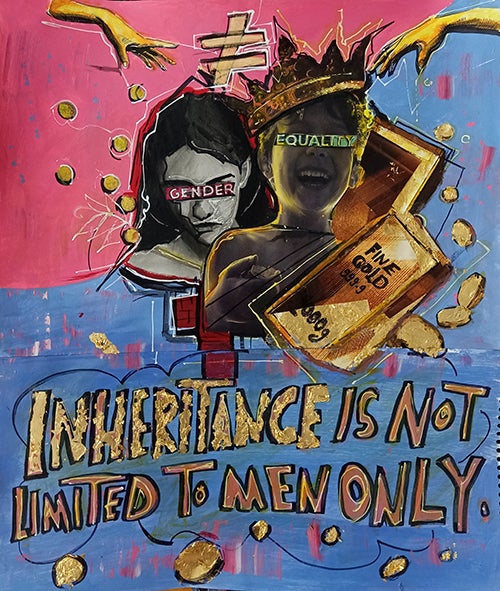

2. Harmful practices are rooted in gender inequality and serve the purpose of controlling girls’ bodies, sexuality or sexual desires.

Harmful practices are often tools of control over women’s sexuality and fertility.

In many places, FGM is thought to supress female sexuality, prevent infidelity or enhance sexual pleasure for men. Though it is sometimes considered a religious obligation, this is “to mask what is at the core, which is controlling women’s sexuality,” said Dr. Hania Sholkamy, an anthropologist at the American University in Cairo’s Social Research Center, who was interviewed in the report.

Child marriage, too, is frequently motivated by the desire to preserve a girl’s virginity for her husband. And son preference, when it is expressed as gender-biased sex selection, is an exertion of social and family preferences over a woman’s fertility.

3. Harmful practices are widespread, cutting across countries, cultures, religions, ethnicities and socioeconomic levels.

Child marriage, FGM and son preference take place around the world. The report includes accounts of child marriage taking place in the United States, stories about FGM from Colombia, Indonesia and Tanzania, and accounts of son preference in Azerbaijan and India, for instance.

Globally, the number of girls and women affected by these practices is staggering – and even, in some cases, growing. This year, 4.1 million girls are at risk of FGM. One in five marriages today involves a child bride. And son preference has resulted in a deficit of some 140 million females.

Although efforts to end harmful practices have seen success, the number of girls subjected to child marriage and FGM is believed to be increasing overall because of population growth in countries with a high prevalence of these practices.

4. The COVID-19 pandemic is likely worsening child marriage and FGM

The pandemic has vast impacts on the lives of girls and their families – from economic hardships and school closures to the loss of access to health services and community programmes.

There is little firm data on how the pandemic is affecting the exercise of harmful practices, but an analysis by UNFPA, Avenir Health, Johns Hopkins University (USA) and Victoria University (Australia) projected that both FGM and child marriage could significantly increase. If the world sees a two-year delay in the implementation of programmes designed to eliminate FGM, an estimated 2 million additional cases of FGM could occur over the next decade that otherwise could have been averted. A one-year delay in programmes to end child marriage, coupled with the pandemic-caused economic downturn, could result in 13 million additional child marriages taking place over the next decade, researchers found.

UNFPA is also starting to see some preliminary indications that both FGM and child marriage are increasing, in at least some places.

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, experts have noted a significant increase in child marriage in Kasai Central and Kasai regions; an assessment of the influence of the pandemic on this trend is underway by local NGOs. And in Tanzania, two of UNFPA’s partners have reported seeing FGM performed in large numbers even though the annual “cutting season” usually does not start until December.

5. We know how to end these harmful practices – and this is the moment to do it

Despite these challenges, the world has seen many promising signs and initiatives showing that it is possible to end harmful practices.

Experience in countries like the Republic of Korea shows that raising the status of women and girls, alongside policy and other changes, can end son preference, for example. And countries like Trinidad and Tobago have had recent success implementing legislative bans on child marriage.

But lasting solutions will require changes to social norms rooted in gender inequality.

UNFPA has released a document “How Changing Social Norms is Crucial to Achieving Gender Equality” designed to help organizations and communities achieve social norms change at scale, and therefore achieve gender equality.

“Beyond providing information and creating spaces for discussion, there is a need to collectively deliberate and explicitly agree to improve the health and well-being of girls and communities, which will support the movement to end the harmful and discriminatory norms,” said Nafissatou Diop, a UNFPA expert in the area of harmful practices and culture. “Context is crucial. There is a no one-size-fits-all approach.”

Right now is the moment to initiate these changes, as the world undergoes seismic shifts due to the pandemic and its social and economic fallout, she added.

“We see how the behaviour of one person can make a difference, how groups of people adopting a certain behaviour influences others,” Ms. Diop said. “We are seeing community influencers from different walks of life, not just political leaders and prominent figures, leading change. Not only does this give us hope, it also proves that collective decisions to shift behaviours can transform norms quickly.”