The United Republic of Tanzania/Malawi

African censuses strive to count everyone

After starting his career as a schoolteacher in the United Republic of Tanzania, Jonas Lubago went to his local bank to open an account but was refused. The reason: He was blind. The bank had a policy of requiring any person with blindness or vision impairment to bring a designated proxy to sign for even the most basic transactions. That was neither practical nor fair, says Mr. Lubago.

Becoming a schoolteacher was Mr. Lubago’s second choice. He entered university with the intention of studying law, but his academic adviser discouraged him from trying because none of the required reading existed in braille. “He told me I would fail,” Mr. Lubago says.

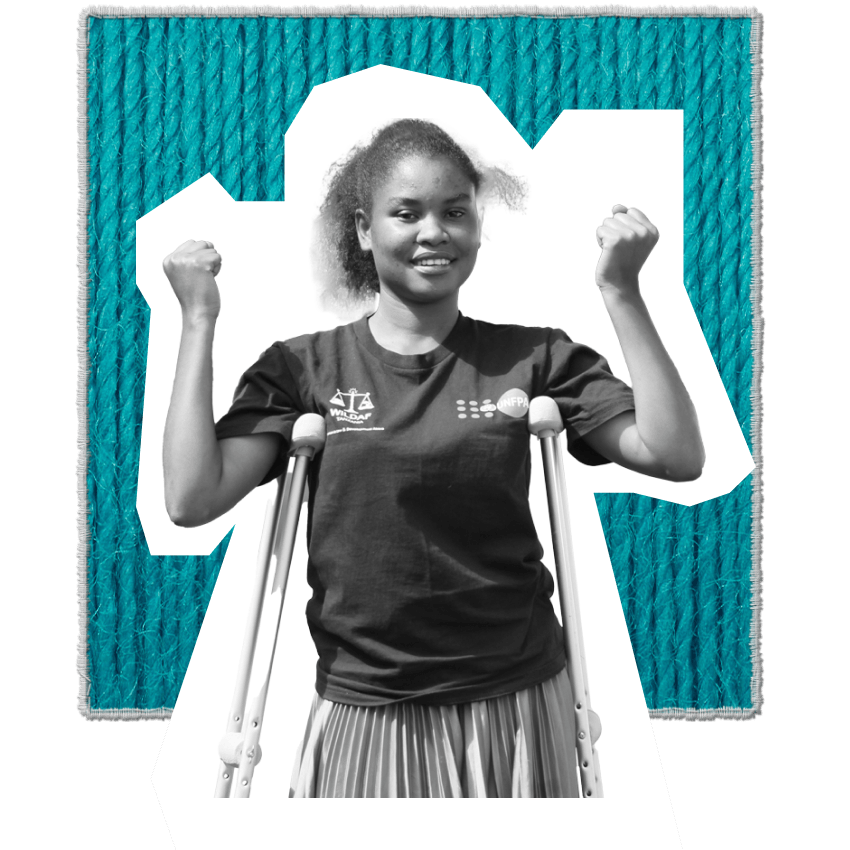

That was two decades ago. While the situation has improved over the years, people with disabilities in the United Republic of Tanzania still face an array of obstacles when they go about their daily lives or need public services, such as health care and education. A clinic may be right around the corner from the home of someone in a wheelchair, but if it is accessible only by stairs, or if the consultation rooms are too small to allow the door to close for privacy, or if the washrooms are not properly equipped, that service is out of reach. “And that’s discrimination,” says Mr. Lubago, who is today the secretary general of the Tanzanian Federation of Disabled Peoples’ Organizations.

In 2012, the country began identifying people with disabilities in its census. Still, the exercise did not count a wide range of disability categories nor did it consider severity. “There was a demand for better data – both from the disabled community and from the Government,” says Principal Statistician and National Census Coordinator Seif Kuchengo.

The information gathered through the census is critically important. As a State Party to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, the United Republic of Tanzania committed to ensuring and promoting “the full realization of all human rights and fundamental freedoms for all persons with disabilities”. Yet institutions require data in order to make services not only available, but also accessible.

Mr. Kuchengo says officials sought early involvement of representatives from the disability community in the design of the most recent census, including in the planning and in the training of enumerators. Mr. Lubago, who left his teaching job, joined forces with government offices to have the census adopt a more expansive and diverse set of internationally standardized disability questions. In all, about 400 people with disabilities and impairments were involved. Some 17 different categories of disability or impairment were included, and levels of severity could also be specified.

Preliminary findings from a 2022 national census show that about 11 per cent of the population has at least one type of physical or developmental disability or impairment, according to Mr. Kuchengo. That level is about 2 percentage points higher than in 2012, but the increase is the result of the recent census’s more comprehensive approach to counting people with disabilities. Mr. Lubago hopes that new census data will show just how large and important the disabilities community is, and result in persons with disabilities participating in local and national decision-making.

In addition to generating better data on persons with disabilities, the 2022 census also included an innovative and more complete count of nomads. Because these communities are constantly on the move in search of food, the government had to reach out to them well in advance to ensure they remained in one place while the census was under way. This meant making sure families had enough food to carry them through the two-day nationwide count.

The United Republic of Tanzania is not the only country generating better data on disabilities. Malawi’s 2018 census, for example, also included albinism among its disability parameters. People with albinism experience multiple forms of discrimination and frequently face risk of violence or death. Since 2006, the United Nations Independent Expert on the enjoyment of human rights by persons with albinism received close to 800 reports from 28 countries of ritual attacks and witchcraft accusations against people with this genetically inherited lack of melanin in the hair, skin or eyes (OHCHR, n.d.c).

Deputy Director of Malawi’s Demographic and Social Statistics Department Isaac Chirwa says, “Many people have problems walking around their communities or even going to school because they fear being attacked.” Before the 2018 census, there were limited data about how many people with albinism there were or where they lived, Mr. Chirwa explains, and without this information, it was difficult for policymakers to take action to make it safe for people to go about their lives and enjoy their rights.

Artwork

Textiles blur the boundary between art and function, practicality and beauty. Women’s movements have long used textiles to draw attention to a range of issues – from body positivity to reproductive justice and systemic racism. Contemporary artists and women-led textile collectives continue this tradition by producing artwork which reflects their local environments and traditions. As it has for thousands of years, textile art continues to offer women around the world the means to connect with previous and future generations of women in their families and communities.

We would like to thank the following textile artists who contributed to the artwork for this report:

-

Nneka Jones

-

Rosie James

-

Bayombe Endani, represented by the Advocacy Project

-

Woza Moya

-

The Tally Assuit Women’s Collective, represented by the International Folk Art Market

-

Pankaja Sethi