While people today live longer, healthier lives than ever before, millions remain far behind on the trajectory of progress.

How factors of marginalization intersect

An individual’s gender can intersect with other aspects of their identity to produce additional layers of discrimination. Choose an example on the left to see how factors such as ethnicity, disability status or income can overlap with gender identity to create unique experiences of marginalization or oppression.

Select a square to see the intersections

How factors of marginalization intersect

An individual’s gender can intersect with other aspects of their identity to produce additional layers of discrimination. Choose an example on the left to see how factors such as ethnicity, disability status or income can overlap with gender identity to create unique experiences of marginalization or oppression.

Select a square to see the intersections

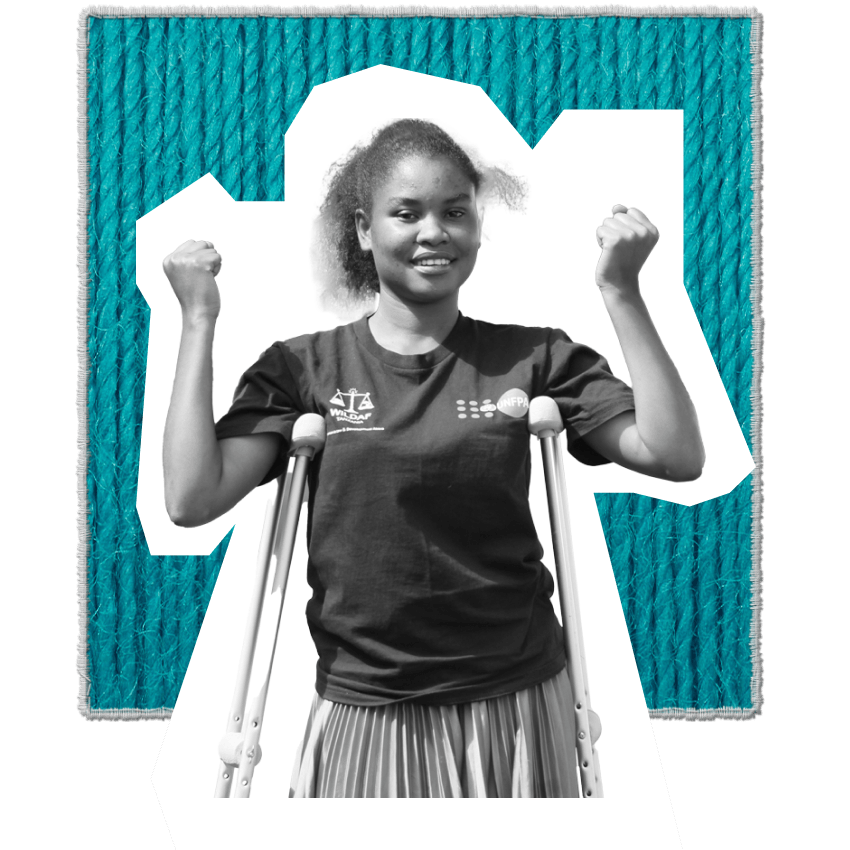

Disability:

Hearing or vision impairment, mobility, mental health

Age:

Children (under 18); Adolescents (10-19); Young adults (18-25); Older adults (over 60)

Migratory status:

Refugees, migrants, domestic workers, people in transit

Location:

Remote, informal settlements, disputed territories

Income:

Lowest wealth quintile

Culture, ethnicity, race, language, religion:

Indigenous peoples, people of African descent, religious minorities, disadvantaged castes

Sexual and gender identity:

Sexual orientation, gender identity, sex traits

HIV status:

Men who have sex with men, sex workers, people who inject drugs, people in detention

Disability:

Hearing or vision impairment, mobility, mental health

Age:

Children (under 18); Adolescents (10-19); Young adults (18-25); Older adults (over 60)

Migratory status:

Refugees, migrants, domestic workers, people in transit

Location:

Remote, informal settlements, disputed territories

Income:

Lowest wealth quintile

Culture, ethnicity, race, language, religion:

Indigenous peoples, people of African descent, religious minorities, disadvantaged castes

Sexual and gender identity:

Sexual orientation, gender identity, sex traits

HIV status:

Men who have sex with men, sex workers, people who inject drugs, people in detention

We need to be able to have jurisdiction over crimes committed on our land. We’re nations within nations, sovereign nations within a nation, and we have the least ability to protect our people.

Carolyn DeFord, United States of America Read storyWhat does it feel like to be left out?

“I need a place to feel home – it’s too hard. You lose yourself, you’re suspended for a long time. You don’t feel you belong anywhere. You feel stateless, forgotten.”

Brian*, age 37

“Discrimination will never end, because that is everywhere. White people, black people, indigenous people, discrimination in food, in clothing, in language, in everything.”

Gertrudis

“I have no insurance. If you have no insurance, you have no medicine, if you have no HIV medicine, you die – finished. I know I have big problems, but I have to try and save my life at least. What should I do now? I can’t go to my country, and I can’t live in this country. I’m not safe.”

Ibrahim*, age 28

“I live in hiding, because we don’t have legal documents, we can’t go anywhere, we can’t work, we don’t enjoy the most basic rights that any human being deserves, like being able to afford to live and access medical aid.”

Azin*, age 45

“When I was pregnant, doctors told me that I was deaf and questioned how I would deliver a baby and appropriately raise this child. However, I now have two children whom I raised on my own.”

Ayjahan, age 35

“I live with my family right now, my mother and brother. I can’t tell them or anyone that I’m gay, because of the stigma. And apart from that, society, I cannot say anything because it’s unacceptable. And also for the state issues. I mean, we are not recognised, we do not have any kinds of rights.”

Efram*, age 30

“We had a spate of violence against people with albinism. Even murder cases.”

Isaac

“I owe my life to the medical counsellor in this centre; without their help I would be dead by now. I owe the fact that I’m here and able to be there for my eight year old daughter to them – I am HIV positive and they helped me access these medicines here.”

Sheri*, age 48

Many people have problems walking around their communities or even going to school because they fear being attacked.

Anastazia Gerald, The United Republic of Tanzania/Malawi Read storyArtwork

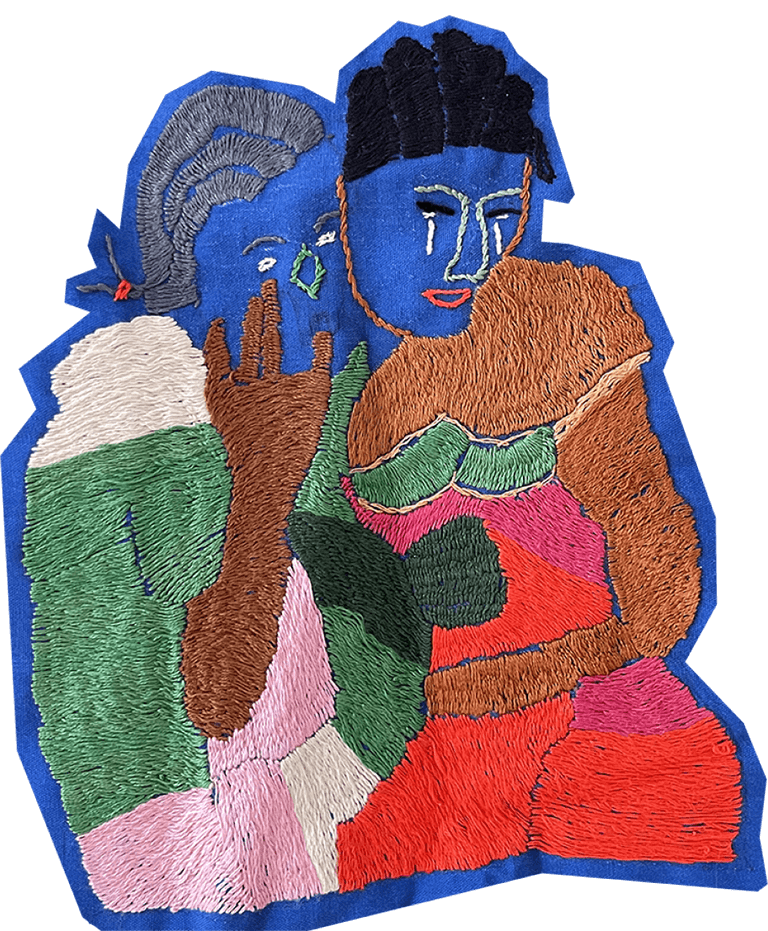

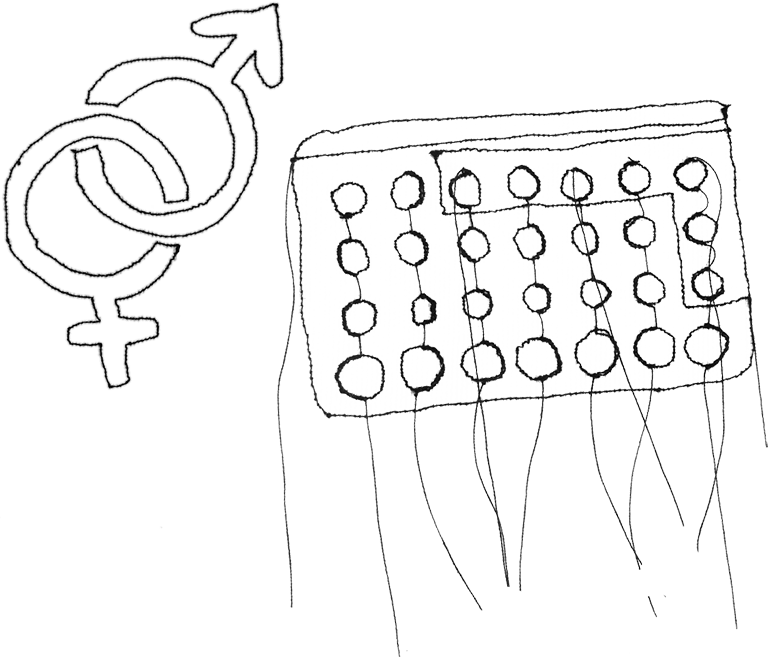

Textiles blur the boundary between art and function, practicality and beauty. Women’s movements have long used textiles to draw attention to a range of issues – from body positivity to reproductive justice and systemic racism. Contemporary artists and women-led textile collectives continue this tradition by producing artwork which reflects their local environments and traditions. As it has for thousands of years, textile art continues to offer women around the world the means to connect with previous and future generations of women in their families and communities.

We would like to thank the following textile artists who contributed to the artwork for this report:

-

Nneka Jones

-

Rosie James

-

Bayombe Endani, represented by the Advocacy Project

-

Woza Moya

-

The Tally Assuit Women’s Collective, represented by the International Folk Art Market

-

Pankaja Sethi