Burkina Faso/Côte d’Ivoire

Local leadership reaches girls most in need

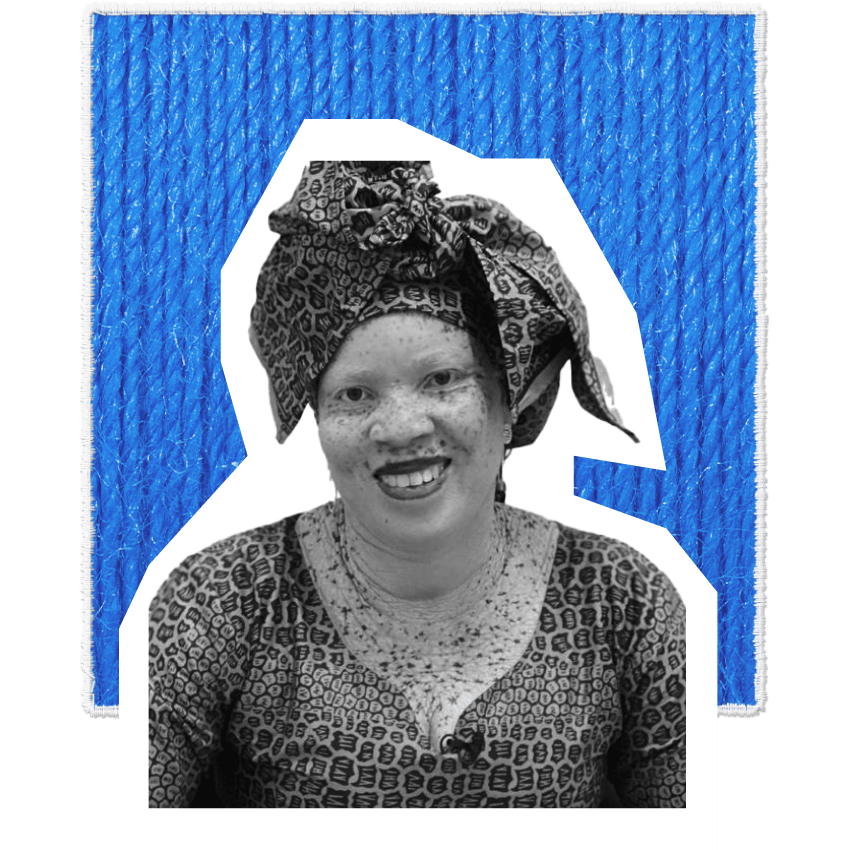

Maïmouna Déné is all too familiar with beliefs and assumptions that undermine equality for women and girls in her community in Burkina Faso. Literacy and labour-force participation are lower for women than men, and gender-based violence and harmful practices are tragically commonplace. But Ms. Déné, 43, has insight into another form of discrimination, one that overlaps with gender: It is, as she says, the “ignorance, social burdens and myths” that affect people with albinism.

Around the world, people with albinism face stigma, exclusion and violence, and in the worst cases can be subject to trafficking, mutilation and murder. Many people with albinism have vision challenges that are not accommodated in school or work settings, leading to high rates of school discontinuation and poverty. The impact on girls with albinism is particularly striking: In Burkina Faso, one third of girls with albinism do not finish primary school (Ero and others, 2021).

The Sahel Women’s Empowerment and Demographic Dividend Project (SWEDD) Project is bringing hundreds of millions of dollars of investment into gender equality initiatives throughout West and Central Africa. But to make the most impact, the programme is engaging closely with local leaders like Ms. Déné, who are able to identify the specific needs of girls and women and how those unique needs can best be addressed.

As the president of the Association of Albino Women of Burkina Faso, she became an ambassador for the “Stronger Together” campaign, a SWEDD Project initiative performing outreach in communities at a local level. Through these efforts, she has been able to secure social inclusion for young girls and women with albinism, in schools and through access to economic opportunities and health care, including sexual and reproductive health and information services. Her association has signed agreements with the health ministry, hospitals, NGOs and other civil society groups, and offers economic training to support young people with albinism and their families. Since it was established in 2008, some 450 women with albinism and the parents of people with albinism have benefited from this training, including 280 who have learned skills in soap making to gain financial independence and help support their families.

Her role as a community leader means she is able to provide support and guidance where it is most needed. That work is intended to help not only people living with albinism today but the next generation as well: “Albinism being a genetic phenomenon, I also fight for my children,” she says.

Syrah Sy Savané, in Côte d’Ivoire, is also acutely aware of the needs within her community. But she is concerned with a very different group of vulnerable girls: those at risk of abduction, forced marriage and female genital mutilation. Ms. Savané, 50, has seen the ill effects of these practices in her own family: “I was raised by my paternal grandmother in Diokoué, a village in the north-west of Côte d’Ivoire. All my aunts suffered early and forced marriage. I was entrusted to them when they were married, I kept them company and saw them very unhappy. I also lost a cousin after she was subjected to female genital mutilation.”

Ms. Savané was fortunate to have an ally in the form of her father, who strongly opposed female genital mutilation. “My aunts wanted to have it done to me too, but my father, who was a teacher, always refused.”

Her experience drove her to become a social worker, before assuming a post in the ministry for women, families and children where, as a child protection expert, she saw how girls were being pulled from school to be married off. The problem, it became clear, was much larger than reaching individual girls. “It was necessary to target not the students, but the parents, who were seeking marriage for their daughters, as well as community leaders and religious guides.”

Today she is applying these lessons in her work with the SWEDD Project. The project plans were written by technicians working in the very communities they were trying to reach, she says. This has proved essential in meeting the specific needs of the girls and their families. Safe spaces, husbands’ clubs and other interventions are making a real difference and, Ms. Savané says, “shining a light where young girls thought they had no rights”.

Artwork

Textiles blur the boundary between art and function, practicality and beauty. Women’s movements have long used textiles to draw attention to a range of issues – from body positivity to reproductive justice and systemic racism. Contemporary artists and women-led textile collectives continue this tradition by producing artwork which reflects their local environments and traditions. As it has for thousands of years, textile art continues to offer women around the world the means to connect with previous and future generations of women in their families and communities.

We would like to thank the following textile artists who contributed to the artwork for this report:

-

Nneka Jones

-

Rosie James

-

Bayombe Endani, represented by the Advocacy Project

-

Woza Moya

-

The Tally Assuit Women’s Collective, represented by the International Folk Art Market

-

Pankaja Sethi