Egypt

Syphilis highlights threat to health and human rights: stigma

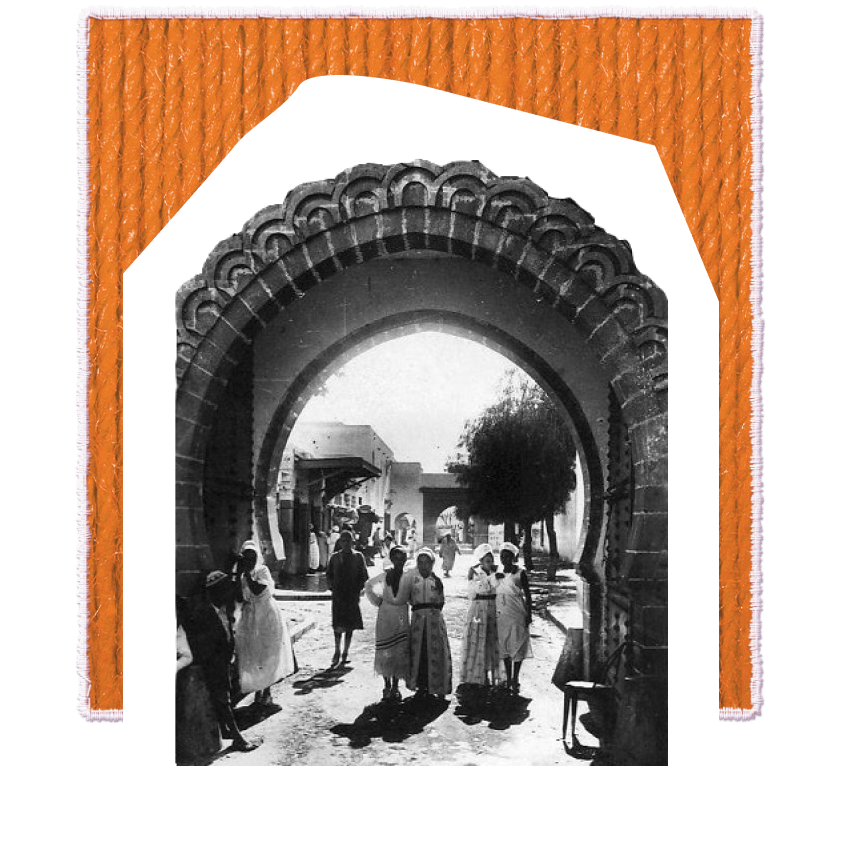

Bousibir was a walled-off brothel in Casablanca, created by colonial authorities as an STI-prevention measure. Historical photograph in public domain.

Syphilis and other sexually transmitted infections are “secret diseases,” says Dr. Adel Botros, a specialist of dermatology and venereology in Egypt, recalling a phone call he received more than 10 years ago. A hospital reached out to report a case of congenital syphilis in a newborn. Dr. Botros rushed to the hospital and asked the father for permission to see the patient – no fee would be charged. Rather than agree, the father left the room; Dr. Botros never saw him again.

Stigma around sexually transmitted infections has long been used to divide communities and reinforce hierarchies – even as it drives people away from health services, perpetuating illness. Syphilis is perhaps the most notorious example of this, having been variously described as “the French disease”, “the Neapolitan disease”, “the Polish disease”, “the German disease”, “the Spanish disease” and “the Christian disease”, among many other names, typically by communities seeking to blame outsiders or enemies for the illness (Tampa and others, 2014).

Today, syphilis – a bacterial infection health officials long hoped would be eliminated by antibiotics – is on the rise around the world. Cases increased from 8.8 million in 1990 to 14 million in 2019, and incidence rose from 160 to 178 per 100,000 people over the same period (Tao and others, 2023).

Yet available data indicate that North Africa and the Middle East have bucked this trend. While rates of babies born with congenital syphilis have more than tripled in the United States since 2016, for instance, congenital syphilis incidence in Morocco has plunged (WHO, n.d.b). In 2022, the World Health Organization announced that Oman had eliminated mother-to-child transmission of the disease (WHO, 2022).

These data defy age-old stereotypes about syphilis in the Arab States region, a history that holds important lessons about disease, gender and power for the modern world, says Ellen Amster, a public health professor at McMaster University in Canada.

“Syphilis was really important in eugenics,” she explains. “Syphilis was considered one of these degenerate things that would destroy a population.” Western colonial authorities described Arabs as inherently vulnerable to it. They even invented a new term – “the degenerate and diseased ‘syphilitic Arab’” – to demonize and diminish Muslims and Arabs, Prof. Amster’s research has shown (Amster, 2016).

“Syphilis was tied to gender disempowerment, to shame around sexuality – which always becomes a gendered shame,” she tells UNFPA. “What the French did to protect their troops from these ‘syphilitic’ native women – in Morocco and throughout the empire – was to create closed brothels that were basically a prison for young women.”

Those efforts were driven by “claims throughout the [Moroccan] protectorate period that syphilis prevalence was like 80 per cent, 100 per cent,” Prof. Amster notes, the result of false positive tests and misdiagnoses of tuberculosis, malaria and other diseases. “They found that when they actually tested women systematically, that syphilis prevalence was 0.5 per cent or less than one half of 1 per cent.”

Modern society has yet to shake off the shame – and power dynamics – attached to contagious disease. In 2022, as global health authorities worked to contain the spread of Mpox (also known as monkeypox), they tried, simultaneously, to contain the stigma swirling around it. Reporting on Mpox “has used language and imagery, particularly portrayals of LGBTI and African people, that reinforce homophobic and racist stereotypes and exacerbate stigma”, UNAIDS warned (UNAIDS, 2022). And illnesses need not be sexually transmitted to provoke intolerance; the COVID-19 pandemic saw waves of anti-Asian xenophobia unleashed around the world (HRW, 2020).

In designing programmes to address contagious disease, issues of power and prejudice must be closely considered. Despite the lessons of history, this remains true for syphilis as well, which is found to disproportionately affect men who have sex with men (WHO, n.d.c.). Communities affected by illness must be engaged, not stigmatized, experts say.

Even in the Arab States region, where comparatively low rates of syphilis are seen today, vigilance is required, both against the disease and against discrimination. In fact, says Dr. Botros in Egypt, the true incidence of sexually transmitted infections like syphilis cannot be known because fear and shame – once weaponized so effectively against the Arab world – persist even now.

“Sometimes we discover a case by coincidence,” Dr. Botros says. “Some patients also don’t come in unless they have no other way to get rid of the problem.”

Artwork

Textiles blur the boundary between art and function, practicality and beauty. Women’s movements have long used textiles to draw attention to a range of issues – from body positivity to reproductive justice and systemic racism. Contemporary artists and women-led textile collectives continue this tradition by producing artwork which reflects their local environments and traditions. As it has for thousands of years, textile art continues to offer women around the world the means to connect with previous and future generations of women in their families and communities.

We would like to thank the following textile artists who contributed to the artwork for this report:

-

Nneka Jones

-

Rosie James

-

Bayombe Endani, represented by the Advocacy Project

-

Woza Moya

-

The Tally Assuit Women’s Collective, represented by the International Folk Art Market

-

Pankaja Sethi